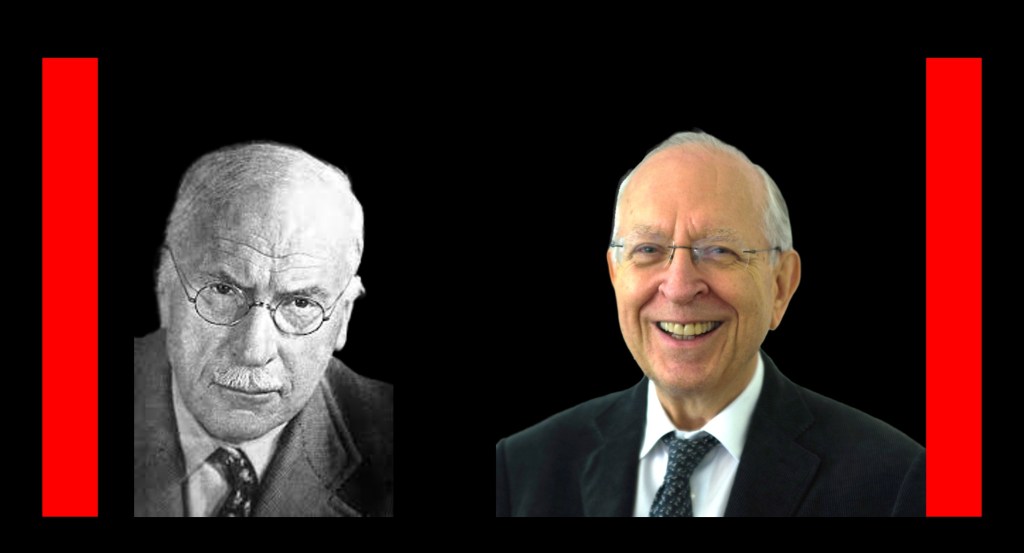

I am a big fan of the work of Carl Jung, and in my opinion the business world could really benefit from his insights. Therefore, I was pleased to have the opportunity to have a conversation with Murray Stein about applying Jungian Analytical Psychology in the workplace.

Murray Stein is a graduate of Yale University (B.A. and M.Div.), the University of Chicago (Ph.D.), and the C.G. Jung Institut-Zurich (Diploma). He is a founding member of the Inter-Regional Society of Jungian Analysts and of the Chicago Society of Jungian Analysts. He has been the president of the International Association for Analytical Psychology (2001-4), and President of The International School of Analytical Psychology (ISAP)in Zurich (2008-2012).

He published tens of books about Carl Jung and analytical psychology, including for instance ‘Jung’s Treatment of Christianity’ and ‘Jung’s Map of the Soul’.

The focus of our conversation was a book Murray edited with John Hollwitz called ‘The Psyche at work – Workplace Applications of Jungian Analytical Psychology’.

We discussed a number of topics, including:

- Individuation and organizations

- The essence of true leadership

- The identity of organizations

- Business ethics

- Embracing the shadow

- Shadow possession and corporate scandals

- The need for self-reflection by leaders

- Executive coaching and psychoanalysis

- The validity of MBTI

- The importance of having a personal North star

I really enjoyed our conversation, which interestingly enough took place on Labor Day, something Jung would undoubtedly label as synchronicity!

If you are interested, you can listen watch our conversation on YouTube or listen to it on Apple Podcasts or Spotify. Follow the links below!

► Episode links: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | YouTube

► No time to watch or listen to the interview? Here is a summary of some of the key points:

Dirk: Why did John Hollwitz and you decide to write a book about applying Jungian analytical psychology in the workplace?

Murray: We didn’t initially set out to write a book; rather, we designed a conference at the C.G. Jung Institute in Evanston, Illinois, in the 1980s. John Hollwitz, a professor at Northwestern University with extensive experience in organizational psychology, convinced me to collaborate on this event. The conference aimed to bring together speakers from both Jungian psychology and the business world, including organizational psychology. From the lectures given by these 8-10 speakers, we selected a collection to publish, and that’s how “The Psyche at Work” came into being. For me, it was my first formal exposure to considering psychology within organizations, as my analytical work primarily involved individuals, though their experiences always revealed much about the workplace.

Dirk: Jung seemed to dislike large organizations, yet individuation, a key Jungian concept, is spiritual growth.1 Could large organizations, despite Jung’s views, serve as excellent platforms or catalysts for individuation by forcing individuals to interact in diverse and sometimes uncomfortable circumstances?

Murray: Yes, large organizations could be places for individuation. An individual working in such an environment must make a fundamental decision: whether to remain true to their instincts and values or to adapt to the organizational culture. This presents a spectrum from fiercely individualistic behavior to complete conformity. Organizations offer a crucial contrast—the “otherness” that forces self-clarification of values, thoughts, and beliefs. Like light needs darkness to be seen, self-awareness emerges from difference. While the overwhelming nature of large groups can crush individual consciousness, leading to groupthink, this context can also trigger burnout or a crisis, forcing a stand against the collective. This process of clarifying one’s position within a social system is indeed a move towards individuation, making one aware of themselves as an individual.

Dirk: John Hollwitz’s essay suggests organizations have psychological lives, collective symbols, and a cultural narrative. Do you believe organizations possess a unique identity that transcends the sum of the identities of their individual members?

Murray: Absolutely, organizations possess an identity that is more than the sum of their individual members’ identities. Individuals join and leave, but the organization persists; corporations, for instance, have an infinite lifespan.2 The organization’s sense of itself—what it stands for in the world and its meaning in the collective—exists beyond the current individuals. Take Ford Motor Company: despite numerous presidents and workers over its long history, it maintains a distinct identity in the collective landscape, recognized globally. This organizational identity is usually established in its early years and, if successful, is maintained by successive individuals. It’s transcendent to the individuals, much like Jungian institutes retain their identity despite changes in leadership.

Dirk: Do you also think that the identity of an organization can change over time, and if so, what would it require, and how would that take place?

Murray: Organizational identity is complex, made of myths and symbols. Starbucks’ worldwide siren logo, for example, is a classic mythological symbol.3 Countries have animal symbols or origin myths, like William Tell for Switzerland.4 Once set, this identity doesn’t change much unless there’s a profound crisis. A country, like the United States currently, can undergo a huge, turbulent transformation that questions its core meaning. Organizations can also experience crises, potentially leading to collapse and reform into a new identity. However, short of such a dramatic collapse or total reorganization, an established organizational identity, with its embedded myths and symbols, tends to persist. Significant change usually requires strong external input like market shifts or crises, rather than internal forces.

Dirk: Jung emphasized the need for self-reflection in leaders, contrasting “so-called leaders” who are symptoms of mass movements with “true leaders” capable of self-reflection.5 What consequences do you foresee for leaders lacking self-reflection, and how might this manifest in organizational performance?

Murray: Jung distinguishes between “so-called leaders,” who are symptoms of a mass movement (like dictators or even figures like Donald Trump who tap into existing collective sentiments), and “true leaders,” exemplified by spiritual figures like Buddha or Moses, who carry their own weight and hold themselves aloof from mass momentum. Leaders lacking self-reflection tend to be the “so-called” type. They don’t provide new vision but rather adopt and represent the organization’s existing identity, aiming for business success. However, without self-reflection, they might fail to steer the organization away from inherent collective biases or risks, leading to disasters like Credit Suisse’s collapse. Self-reflection, at a high level, allows a true leader to introduce new directions based on deep convictions, even if constrained by the organization’s immense size, as Obama noted about the US government.

Dirk: What would you recommend for leaders who want to develop their self-reflection? What are practical ways they could work on it beyond traditional analysis?

Murray: The first step for developing self-reflection is engaging in analysis, which is an exercise in reflection. However, for organizational leaders, a “reflective leader” would also reflect on the organization itself. Executive coaches can facilitate this by helping leaders reflect on their leadership style, team building, and responsible distribution of duties.6 Beyond financial interests, leaders now increasingly reflect on social responsibility, considering the community impacted by their operations. A good executive coach, especially one with depth counseling or psychotherapy training, can help leaders explore their personal complexes (like mother or father complexes). These complexes influence judgment and can create biases, potentially causing leaders to avoid necessary challenges. By reflecting on personal history and its influence, leaders can gain insights into their choices, the people they choose to work with, and the risks they take or avoid.7

Dirk: Executive coaching is popular, but it’s often shorter and more surface-level than in-depth psychotherapy. What do you see as the possibilities and limitations of executive coaching for individuals and organizations, particularly in fostering deeper self-awareness?

Murray: The possibilities and limitations of executive coaching largely depend on the coach’s training and the client’s openness. A coach with training in organizational psychology, depth counseling, or even psychotherapy can offer greater depth. Understanding psychotherapeutic principles like projection, complex enactments, and Shadow awareness (personal and collective) enables the coach to guide the client further. While an executive coach isn’t a psychotherapist, incorporating these principles can deepen the coaching process. However, the client’s willingness to engage in personal work—delving into personal history, family dynamics, or the “shadow” aspects of organizational life—is crucial. Some clients eagerly explore these areas, while others shy away. Ultimately, the effectiveness of executive coaching in fostering deeper self-awareness hinges on both the coach’s skill in taking the client there and the client’s readiness to go.

Dirk: Do you think psychotherapy and executive coaching could be complementary? For instance, if someone is in analysis for deep self-reflection and also receives more instrumental coaching, could that combination work, or might undesired interferences occur?

Murray: I believe that psychotherapy and executive coaching could work quite well together, complementing each other. The key would be the comfort level of both the executive coach and the Jungian analyst with such an arrangement. If both professionals are open to the client engaging in both types of reflection, and if they can coordinate or at least acknowledge each other’s roles, there’s no inherent reason for undesired interferences. In fact, the deep personal work of analysis could inform and enrich the more instrumental focus of executive coaching, and vice-versa, leading to more holistic development for the client.

Dirk: Jung wrote about the limitations of human leadership, stating leaders are subject to “great symbolic principles.”8 Which symbolic principles do you think Jung would refer to, and how could this manifest in the business world?

Murray: Jung would likely refer to corporate myths as symbolic principles influencing leaders. A corporate myth is the overarching story or narrative a company tells about itself to the wider world—its history, founder’s ideology, and self-perception. These symbolic principles inherently limit a leader, as they step into an existing, larger narrative. However, awareness of this myth can also empower leaders to use it effectively. Furthermore, leaders can reinterpret these myths, giving them more contemporary or broader meanings, much like an analyst reinterprets a dream to offer new perspectives. This means working with the existing symbolic framework to adapt and guide the organization, rather than being entirely controlled by it.

Dirk: The business world has been plagued by corporate scandals. How could embracing their “Shadow” help organizations and business leaders prevent these scandals?

Murray: Embracing the Shadow in an organizational context means becoming aware of its existence. In analysis, awareness is the first step toward remedial action. Many businesses contribute to scandals by ignoring or sweeping their shadowy aspects under the rug, such as the profit motive overriding ethical considerations (e.g., selling addictive opioids despite knowing the harm). They are not “embracing” the shadow, but actively looking away. To truly see the Shadow, a leader must reflect, turn inward, or seek external perspective. Once conscious of the potential for harm or unethical practices, an organization can then decide whether to continue that course—but at least it would be a conscious decision, rather than an unconscious enactment of the Shadow. Leaders who acknowledge and take responsibility for the potentially damaging aspects of their organization’s history or current practices can then make informed decisions to prevent future scandals, even if it requires confronting uncomfortable truths.

Discover more from Dirk Verburg

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.