Many high performers are inclined to take on too much responsibility. These people are often a dream for the companies they work for: in addition to being dedicated and hardworking, they are always willing to go the extra mile. However, as a result, a number of them experience serious work-life balance issues, and some even suffer from mental and/or physical health problems.

These issues do not stem from the content of their work; they all like their work. Instead, these issues stem from the fact that they assume responsibility for elements in their work that they cannot control.

A Blast from the Past: Stephen Covey

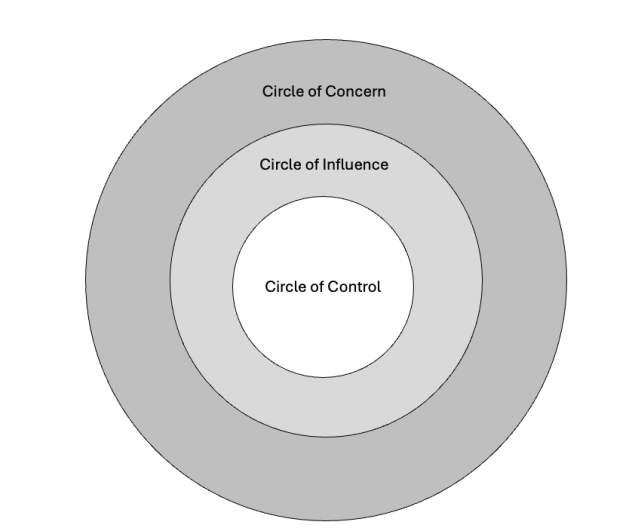

An interesting framework to categorize the issues we are confronted with is the three circles Stephen Covey introduced in his book, The 7 Habits of Highly Effective People. Although the book and the author feel a bit “stale” nowadays, the model remains a very useful one.

The first circle is the Circle of Control. Here we find the issues that are firmly in our control. On a personal level, this includes our eating and exercising habits. On a professional level, it includes our behavior in the office and the quality of our work.

The Circle of Influence comprises issues that we cannot control but only can, as the name suggests, try to influence. In this circle, we can find, for instance, important projects for our organization that are managed by colleagues, or strategic decisions taken by the leadership of the organizations we work for.

Finally, there is the Circle of Concern. Here we find issues that are firmly outside our control and almost impossible to influence as individual beings, but can nevertheless affect us. Examples include climate change, wars, and the outcomes of elections.

The theory of Stephen Covey is that we should identify areas within our Circle of Concern where we can exert influence through proactive measures. However, that is exactly where responsibility problems starts!

The Problem Is the Circle of Influence

Those of us who are inclined to take on too much responsibility never struggle with taking ownership of issues in our Circle of Control. Unhealthy eating habits, not enough physical exercise, a bad relationship with a colleague or our manager? We will readily admit that it is our problem and that we will need to take action.

At the same time, we are intelligent enough to understand that we cannot be individually held responsible for solving the issues in their Circle of Concern.

Instead, for those of us who are inclined to take on too much responsibility, our problems stem from the fact that we do not recognize that our responsibility is limited to our Circle of Control and does not extend to our Circle of Influence.

As a result, we are inclined to assume the mental responsibility for issues we cannot control but will try to control anyway. In the workplace, this means we will mentally take ownership of issues that should be addressed by others, for instance by our peers, line managers, or the senior leadership of the organzations we work for.

Potential Problems As A Result Of Not Observing Our Boundaries

This ‘mental ownership’ can lead to a number of problems:

- Workload – The volume of work might become too big for us to handle, which can have a negative impact on our work-life balance, and potentially on the quality of our own work.

- Interference in the work of others – Peers and managers might look unkindly on what they rightly regard as our interference with their Circle of Control

- Prolonging the Problem – By assuming responsibilities in areas we are not responsible for, the need to act by the people who are responsible is taken away. After all, if a parent always cleans up after their teenagers every time they make a mess of their bedroom or kitchen, what is the incentive for these teenagers to clean up?

- Resentment – After addressing the problem, feelings of resentment can flare up, especially regarding the leadership of our team or organization. If we save a project that one of your peers is responsible for, what is the incentive for our leadership to urge our peer to step up? We already solved their problem, so why would our leaders create a new one in the form of having a difficult conversation with our peer? Because it is “the right thing” to do, and we would have done so if we were in their position? Really?

- Unrealistic expectations – Finally, there is the danger that we expect to receive the same loyalty and dedication that we invest in organizations back from these organizations. This expectation might prove to be unrealistic, especially in times of leadership changes and reorganizations

Should We Just Ignore All Problems Outside Our Circle Of Control?

Now, do not get me wrong. Having a sense of responsibility is a good thing; our families, societies, and organizations need people who take responsibility outside their circle of control (ever heard of Mahatma Gandhi, Martin Luther King, or Mother Teresa?). However, and this is key, this needs to be a conscious choice.

A Conscious Choice

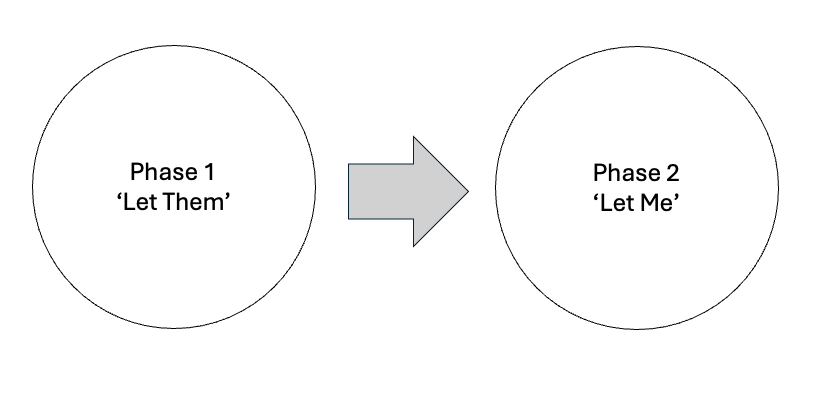

I recently read The Let Them Theory by Mel Robbins. Mel Robbins recommends splitting the decision-making process about taking action in areas we are not responsible for into two phases:

Phase 1: Let Them: “Not Your Problem”

In the “Let them” phase, we decide that a particular issue is not our problem and that we do not have to take action. All we have to do is to focus on controlling our own reaction instead of trying to control other people’s behavior (which we cannot control anyway), no matter how annoying or stupid we think it is.

Examples in the workplace include no longer questioning why our colleague does not step up to their responsibilities or why our manager does not take decisive action to mitigate a serious issue.

This sounds easy, but it might actually be quite hard if we have a big sense of responsibility and do not clearly see the distinction between our Circle of Control and our Circle of Influence.

Do you want to practice? Start small, for instance, by breaking your habit of always volunteering for the things you typically volunteer for at work. The reason is that we need to experience the sensation of actually having a choice.

Phase 2: Let Me: From “I Have to” to “I Want to”

In the subsequent “Let me” phase, we choose to react in the way we want to react.

We can decide to ignore the problem that is not ours in the first place and let those who are responsible for it deal with it. Alternatively, we can consciously decide to influence the situation by addressing the issue. Both are acceptable.

However, if we decide to start influencing, we need to be aware that we might not get any credit, may not be able to solve the problem, could create a lot of irritation, and run the chance of becoming involved longer and more deeply than we originally envisioned.

That is perfectly fine as long as we consciously choose this. If we do not wish to deal with these consequences, then we should not start to influence, or at least not complain about the consequences of our decision to influence. After all, it is not our problem anyway.

The key is to mentally move ourselves from “I have to” to “I want to.”

Discover more from Dirk Verburg

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.