The Power of debate in the public domain

The invention of the printing press proved to be a pivotal point in the development of our society because it enabled the dissemination of ideas and information at an unprecedented pace. It is unlikely that, without the printing press, the Reformation in the 16th century would have had such a huge impact, so quickly.

In the 20th century, radio and television increased the speed of information even more. It is likely that the public opinion about the war in Vietnam (the first television war) changed significantly as a result of the coverage of this war on television.

Social media emerges

No wonder that many governments tried to control these media, either in the form of censorship, or by creating monopolies for news dissemination (e.g in the former Soviet Union).

At the end of the 1990s, social media platforms started to emerge, disrupting the traditional media landscape of newspaper, radio, and television organizations.

Before the invention of the World Wide Web in 1989, the media industry had relatively high entry barriers. Equipment and/or access to distribution networks was expensive, and often regulated by national governments through licenses. Traditional media companies were used to playing the role of a ‘broker’ or middle man: they decided which events were newsworthy, and how these would be covered.

Social media, on the other hand, enabled everyone with a computer and an internet connection with the possibility to share their views and ideas with the public at large. Therefore, one could consider social media the ‘printing press 2.0’.

The bad reputation of social media

Until a couple of years ago, social media had a progressive image. It was associated with hip and (supposedly) progressively thinking, California-based technology companies. Former president Barack Obama was praised for his innovative use of social media (especially Facebook) in his 2007-2008 campaign.

This perception changed because of the use of social media in the 2016 presidential election campaign of Donald Trump (the Cambridge Analytica scandal).

Ever since, social media platforms like Facebook and Twitter are the subject of vehement discussions around ‘fake news’ and ‘hate speech’. In the case of Facebook, this has even led to a #DeleteFacebook campaign.

The broader picture

The broader picture is that a number of governments, and other stakeholders in our society, increasingly want to restrict Internet companies in terms of the content they make available to users.

A quick and completely arbitrary selection:

- Pakistan is toying with the idea to implement some of the strongest forms of internet censorship in the world;

- The EU has implemented a law restricting the information people can upload, and forces Netflix to ensure 30% of its content consists of European productions;

- Turkey wants to implement a new law on social media;

- Russia implements legislation and a technical infrastructure to block content the government has banned, and reroutes internet traffic;

- The Chinese government selects what its citizens can see on the internet;

- North Korea only makes a limited number of websites available for citizens that have an Internet connection;

- The Ukraine blocks social media from Russia;

- Activists want to ‘deplatform’ far and alt-right speakers from social media;

- A progressive academic wants to force tech companies to create a USD 10bn ‘trust fund’ to sponsor ‘the organizations they’ve undermined: journalism, fact-checking, and media literacy’

- Social media companies have become much more critical regarding the content they allow on their platforms

Although the motives and causes might be completely different, these developments have one thing in common: they limit both the possibility, as well as the responsibility for end-users to select what they want to see, by reintroducing the role of a (virtual) middle man.

A polarized world

These developments fit the picture of the increased polarization we see in the world around us. Both between societies, as well as inside our Western society.

Polarization between societies, because we seem to be a long way away from the predictions of Fukuyama’s book ‘The End of History and the Last Man‘ (1992). This book, written after the collapse of the Soviet Union, predicted a new world order, in which Western liberal democracies and capitalism would be the only remaining organising principles on a global level.

Polarization in our Western society, because it seems we moved on from valuing each other as human beings having a political opinion, to people being valued according their political opinions. An excellent description of the way Republicans and Democrats have started to treat each other in the US can be found in David Zahl’s book ‘Seculosity‘.

As a result, we ultimately do no longer consider opinions as right or wrong, but the people who are having them as being right or wrong. In its most extreme form, this can lead to people feeling they have legitimate reasons to kill others who ‘are wrong’ (e.g. the murder of politicians like Pim Fortuijn in The Netherlands, Jo Cox in the UK and Walter Lübcke in Germany).

Nostalgia

Nowadays I almost get nostalgic feelings about going to college in the Netherlands at the mid 1980s. The Netherlands was still a compartmentalized society at the time: Protestants, Roman-Catholics, Socialists and Liberals each had their own primary and secondary schools, newspapers, broadcasting organizations, youth clubs, sports teams, etc. However the vast majority of colleges were neutral. I remember vividly what a great experience it was for me and my fellow-students when, at college, we finally met people who had a different religion (or non) and political conviction.

During our years in college, we vehemently debated our religious and political differences 24/7 (I am sure I and my fellow students are nowadays extremely happy our debates have not left a digital trail!). Nevertheless, we considered our friendship, camaraderie, fun and shared interests in books, music and movies, as far more important than our religious, political and intellectual differences.

How different is this from today, where the most important factor for college students in the US to choose their roommates seems to be a shared political conviction.

A false choice

The increased polarization in our Western society seems to find a nucleus in debates about which opinions should be allowed on the Internet and social media, and what not.

Ultimately the binary choice we seem to be confronted with is: what is the bigger evil? Allow the distribution of ideas on the Internet which we would never accept in traditional media (e.g. racism, homophobia or calls for violence), or accept censorship?

A third way for open democratic societies

I think there is a third way.

In my view, the unique feature of open and democratic societies is the possibility to have debates.

These debates can ultimately lead to legislation about which opinions we do, and which ones we do not allow in the public domain. Not allowing this debate to happen on social media is in my view not helpful for the development of open democratic societies.

Free speech is the whole thing, the whole ball game. Free speech is life itself. (Salman Rushdie)

Open, democratic societies need to do three things to allow these debates to take place:

- Education – First of all, society needs to educate students that differences of opinion are part and parcel of living in open society, and the fact that we can have and express these openly, is a great good, which needs to be protected. Examples of regimes and societies where this is or was not the case, might be helpful to illustrate this fact. Furthermore, students should be stimulated to form their own opinions on the basis of data and research, rather than slavishly adopting the opinions of others (including those of their teachers and professors). Finally they need to be educated about the media landscape, and learn to judge the trustworthiness of news outlets for themselves.

- Media outlets – Secondly, established media outlets would do well to value different opinions. As much as I like for instance the New York Times and the Economist (to name a few), their opinions are quite predictable. According to the New York Times, Donald Trump is the root of all evil; according to the Economist, all problems in the world can be solved by free trade and market mechanisms. Valuing different opinions usually starts with not taking them at face value, but trying to understand where they are stemming from.

- Legislation – Finally, I think the content on the Internet in open democratic societies needs to be governed by the national laws of these societies. If these national laws do not allow child pornography, discrimination (whether based on gender, race, religion or sexual preference), deying the holocaust (e.g in Germany and Austria), or calls for violence, governments have the right to ban this content from the Internet in their societies.

However, if these national laws do not prohibit blasphemy, weird conspiracy theories or the expression of anti-nationalistic feelings, people should feel free to air them, also on the Internet.

After all, there are not many historic examples where censorship contributed to a happier society. On the contrary…

“Censorship reflects society’s lack of confidence in itself. It is a hallmark of an authoritarian regime.”

Potter Stewart

© Dirk Verburg 2020

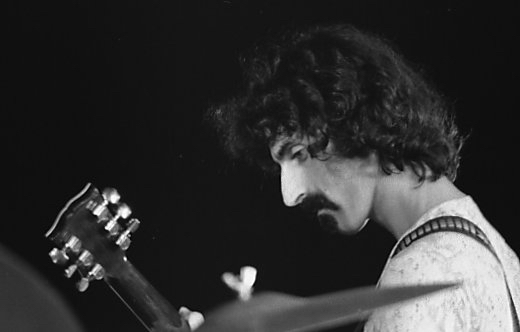

Photo credit: By Jean-Luc – originally posted to Flickr as FRANK ZAPPA, CC BY-SA 2.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=6798755

Cartoon credit: Daniel Paz