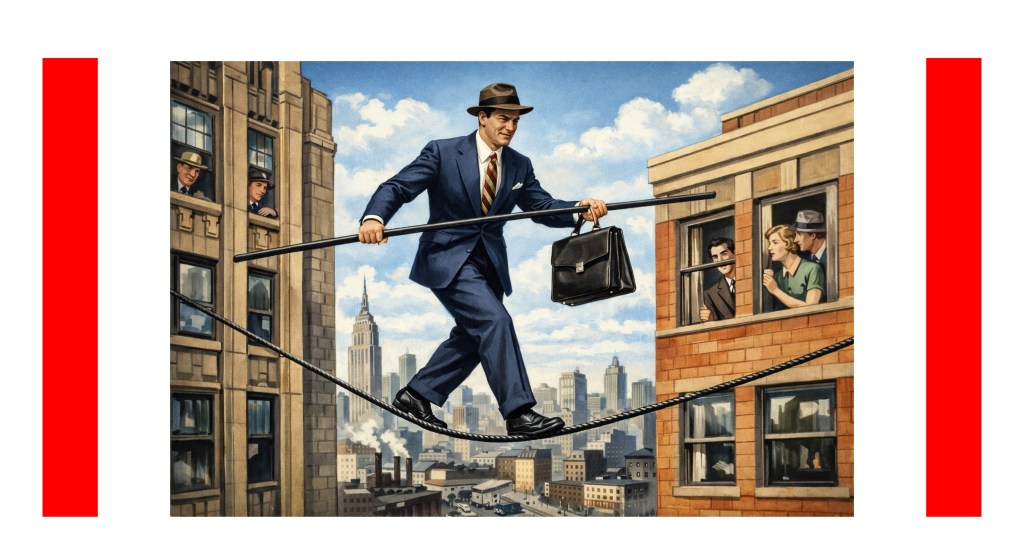

The statistics around executive transition failure rates of newly appointed executives are staggering:

- Nearly half of all leadership transitions fail (McKinsey)

- Not only external hires fail: research from DDI shows that 35% of all executives promoted internally are considered failures

- The costs of C-level failures are, in the vast majority of cases, higher than USD 2 million, but can be as high as USD 30 million. In their Harvard Business Review article, Claudio Fernández-Aráoz, Gregory Nagel, and Carrie Green estimate that the costs of mismanaged CEO transitions in the S&P 1500 alone already result in nearly USD1 trillion in market value loss on a yearly basis.

Unfortunately, the number of leaders and organizations that actually invest in addressing this problem is relatively small. And that is an issue for both the individuals concerned and their organizations.

“It’s the culture, stupid!”

My transfer as a a senior HR executive from the oil and gas industry to the financial services industry provided me with insight into the complexity of inter-industry transfers. I assumed “HR was HR,” and that the industry would not have a significant impact on the way I needed to manage my function.

That assumption proved to be wrong.

What I did not understand at the time was that the oil and gas industry is fundamentally different from the financial services industry, and that this difference had a major impact on the HR agenda.

Timelines

The oil and gas industry typically works with long timelines. On average, it takes three to five-plus years to build relationships with national governments to obtain a 20- to 40-year license to explore and drill for fossil fuels. Quarterly results announcements are sometimes “non-events” because the most important parameters are the oil price and the reserve-replacement ratio.

In contrast, the financial industry typically works with much shorter cycles—in the case of trades, sometimes even as short as minutes or seconds. Quarterly results, for instance, are, therefore, much more important when judging the state of financial services companies.

Teams vs. Individuals

Successfully obtaining a license to explore and drill for oil & gas requires navigating a series of unique, complex political, financial, legal, and technical situations that can only be managed effectively by multidisciplinary teams.

In contrast, success and failure in the financial services industry are much more attributable to individual decision-makers. This is why the movement of senior executives in this industry has a significance similar to that of professional soccer. If an executive in the area of M&A switches from Bank A to Bank B, the impact on Bank B’s performance can be similar to a soccer team acquiring a new star player.

Now, no industry is better or worse than another; they are just different. What I learned was that my assumption that “HR was HR”—and that I could simply “cut and paste” my style and agenda from one industry to another—was incorrect.

Challenges transitions pose

In the personal example I shared above, it was clearly the culture I had to adjust to; other factors include, for instance, the nature of the organization, biases, and expectations (specifically “quick wins”).

Culture

Although this often is considered to be a “soft” factor, in reality, it is not. On the contrary, it determines daily life in organizations and has a deep impact on which behaviors work, and which ones do not. For instance:

- Trust – Is trust given, or does it need to be earned?

- Peers – In which areas do peers see each other as colleagues, and in which areas do they see each other as competitors?

- Risk Appetite – Are people rewarded for taking risks (and occasionally getting it wrong), or for playing it safe?

Getting this wrong in the beginning can have major and lasting implications, especially from an impression perspective. Ideally, a match between the candidate and the organizational culture is made beforehand; however, if not, help might be required to assist the new entrant in understanding the culture.

Nature of the organization

I had the pleasure of working for corporates, scale-ups, and start-ups. All these companies work fundamentally different.

From ‘whatever works’ (start-up), to ‘we need to structure X without becoming bureaucratic’ (scale-up), to ‘this is just not the way things work around here’ (corporate). These differences require leaders to pivot their management styles to suit the stage in the maturity of the organization.

Biases

Biases can stem from what people read or hear about an organization and its industry, even before they participate in the recruitment process. However, candidates usually pick up much stronger biases from the people they meet during the hiring process (e.g., the headhunter, the supervisory board, senior business and HR leaders).

These biases typically center around business topics (“You need to sort out Product Line A; I doubt it’s ever going to fly”) and people (“I would recommend you take a close look at whether X is the right person on your team; I am not sure whether (s)he’s cutting it. However, as you will see, Y is just great.”).

The danger is that these biases are internalized by new leaders without proper reflection, especially since they might (subconsciously) feel they “owe” the decision-makers involved in their selection and appointment. As a result, they often start their roles with a strong confirmation bias.

Expectations and “Quick Wins”

Another challenge involves the expectations of senior leaders or, in the case of CEOs, the supervisory board. In my conversation with Ty Wiggins about his book ‘The new CEO‘, Ty stressed the need to make these expectations explicit. A statement like “We need to move into the Chinese market,” for instance, is highly ambiguous in terms of content and timing.

The best way to make these expectations explicit is to run the risk of being perceived as “not getting it”, and ask the classic question: “What does success look like (and when)?”

A special point of attention is the pressure to deliver “quick wins.” There is an unwritten rule that, in their first three months, problems of an executive belong to their predecessor; after that, they are owned by the new executive. No wonder many executives start looking for “low-hanging fruit” as soon as their “first 90 days” (the title of Michael Watkins‘s famous book on this topic) clock starts ticking.

This pressure creates the risk that newly appointed executives will make changes without due process—changes that might not be in the interest of the executive or the company further down the road.

How to ensure a successful transition?

A successful transition consists of two parts: a thorough selection process and a transition period aimed at ensuring success.

In the selection process, both capability and cultural fit must be tested. Testing the capability is the responsibility of business leaders. Regarding the cultural fit, HR leaders play a major role. They know which behavioral skills are required to be successful in their organization.

The second part is transition coaching. A good external transition coach brings objectivity, time, focus, a proven methodology, and pattern recognition from seeing dozens of transitions.

Why companies and new executives do not invest in transition coaching

Unfortunately, for various reasons, many companies conduct a thorough selection process but do not invest in transition coaching.

The first reason is that many executives do not think they need it and believe they can beat the statistics: “I never needed this kind of support earlier in my career; why would I need it now?” This assumes there are no special circumstances that distinguish this move from earlier moves. As with all assumptions, it is worth testing. As many executives can testify, moving up the hierarchy or changing industries and companies often means the game changes, and a different set of rules applies.

The second reason is pride: “I’ve got this.” Asking the company for a transition coach—or privately engaging one—is often seen as a sign of weakness: “They pay me $X per year; I should be able to do this.”

Furthermore, many senior leaders involved in the hiring process do not see the need either. After all, they likely did not have this support, so why would others? Often, there is an element of an initiation rite—especially in high-testosterone, Darwinian cultures—that can be compared to a “trial by fire”: “Now let’s see what you are made of!”

Risk Management

The irony is, of course, that organizations spend months recruiting executives and invest huge amounts of money in headhunter fees, only to leave the actual transition to chance. Therefore, the next time you are onboarding a senior executive, it is worth asking: Should we invest in their success, or just hope they will figure it out?

(Source illustration: ChatGPT)

Discover more from Dirk Verburg

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.