A number of change initiatives in organizations do not add, but rather destroy value. In this post, the reasons for this are explained and recommendations are given on how to prevent the launch of such initiatives. Concrete examples are provided to illustrate the issues.

Change has become a necessary and constant factor

In 1965 Bob Dylan wrote the iconic song ‘It’s Alright, Ma (I’m Only Bleeding)’ with the prophetic line: ‘He who is not being born is busy dying’.

The ability to ‘Being born’ is not only important for individuals, the capability to effectively change (or transform) the organization based on changes in its environment, is also vital for organizations.

Organizations that do not adapt themselves in the right way and at the right time to changes in their environment often cease to exist, with all the associated broader economic and social consequences.

Fortunately, most organizations are equipped with leaders who realize this and are able to initiate and implement changes in their organizations in an effective manner. If they are under the impression that they are not capable of handling this effectively themselves, can elect help out of the armies of external consultants on the market who are more than capable and eager to assist.

Change for the sake of change

So if changes are necessary and most organizations are able to handle them effectively, what is the problem?

The problem is that many change initiatives do add, but destroy value. These initiatives are initiated for the wrong reasons, have a negative effect on the motivation of employees, and destroy shareholder value.

What are some of the typical situations in which these non-functional change initiatives (change for the sake of change) take place?

- Changes that do not solve the strategic challenge – Organizations’ decision-making processes are not always equipped to adequately react to the economic, political or technological developments they are confronted with. Often driven by a lack of sense of reality or a focus on preserving their own positions, rather than addressing the root cause of the crisis, leaders of these companies embark on a raft of activities and initiatives that do not address the strategic challenge they are confronted with. Although the activity level of project management offices in these companies can burst through the seams, the positive impact on the final destination of the company is zero. Historic examples include Nokia, Blackberry and Kodak.

In professional services companies where the largest part of the staff has direct contact with clients, the majority of the staff will immediately analyze how planned changes impact their work by asking themselves the question: ‘does this change makes it easier or harder for me to conduct business with my clients’? If it is the latter, they are likely to start looking around for other opportunities. This problem is less likely to occur in large industrial organizations where the core business of the company consists of dealing with complicated technological and commercial choices (e.g. Pharma, Automotive and Aerospace companies).

- Change of leadership – In some companies, there is a ‘built-in’ expectation in the culture that newly appointed leaders will, after their first 90 or 100 days, replace a number of their direct reports and/or make other radical changes to the organization, regardless of the fact whether there is a real need or reason to do so or not. This expectation can live inside the organization, externally or both. An example is the shake-up of Credit Suisse in 2015 by its new CEO. Failing to live up to this expectation often has a negative effect on the leader concerned: instead of praising his prudence and thoroughness, the decisiveness of the leader is called into question.

- Fashion – Just like there is a market for consumer products susceptible to trends and fashion (e.g. clothes), there are also trends on the corporate initiative market. Historic and current examples include Information Planning, Kaizen, Just in Time manufacturing, ERP systems, Sensitivity Training, Balanced Score Cards, Activity Based Costing, Total Quality Management, Core Competences, CRM, Six Sigma, Shared Service Centers, Design Thinking, Agility, etc. In the same way that consumers quite often have the impression that buying certain products will vastly improve their lives, business leaders also have the idea that adopting certain trends on a large scale will vastly improve the performance of their organizations overnight. The psychological mechanism through which these trends are sold (often labeled as ‘solutions’) by internal stakeholders and external consultants, is often similar to the way consumer products are sold, i.e. by sellers who make unreasonable claims in terms of the effect(s) the product will have and buyers who happily make one or more leaps of faith to believe this. This does not mean all these trends or solutions are wrong, but it does mean that decision makers in organizations seriously need to consider if, and for which purpose, they want to adopt a specific methodology.

- Peer pressure – This factor is related to the one above. Keeping up with the Joneses exists in the corporate world as well. ‘I heard our competitor launched an XYZ program. Should we not do something similar?’.

Consequences of failed change initiatives

A number of organizations and decision-makers fail to realize that, in addition to the visible costs (e.g. for external consultants), there are often hidden costs associated with these non-essential changes, stemming from a loss of productivity, customer focus, motivation, cynicism and fatigue.

- Loss of productivity – In the shorter term, productivity may suffer as a result of the fact that employees will need to spend time and energy on dealing with the change program instead of focusing on their core activities. They may need to attend ‘town halls’, workshops and other meetings. They may even have to worry about the content or, in the worst case, the future of their jobs. To put it crudely, if a company employing 1.000 employees whose total costs of employment are $1.000/day, wants all its employees to spend one day on a particular change-related activity, the costs for the company are $1.000.000 on an annualized basis (ex. facilitation and T&E costs). This means the return on investment should be more than $1.000.000 to justify this event.

- Loss of customer focus – The vast majority of organizational change initiatives does not benefit external customers directly, but only indirectly, or with a time delay (e.g. headcount reduction programs do not immediately result in lower costs, and even customer service programs hardly ever show instant results). This means in the vast majority of cases that ‘real-time’ time and energy is usurped by internal activities rather than spent on serving clients and their issues.

- Loss of motivation – Almost all changes involving headcount reduction lead to a loss of motivation of employees before, during, and after the implementation of these changes. The reason why the motivation of employees who are affected by the change suffers is clear. However, it is interesting to see that also the motivation of employees that are not affected suffers. A number of them will often leave the organization as a direct result of a reorganization, which has not even affected them because the psychological contract with their company is broken.

- Cynicism towards management – Cynicism should be expected if employees cannot be convinced of the necessity or usefulness of the changes, and/or if they see a discrepancy between the way in which leaders talk and the way they act. This cynicism usually goes hand in hand with a loss of credibility of the leaders and can undermine the long-term trust relationship between the employees and their leaders. It is hard for the employees to understand why their leaders cannot see or admit that the emperor does not wear clothes.

In a leading professional services organization, the dominant management style can be described in terms of a combination of ‘management by fear’ and ‘micro-management’. Employees who make mistakes are punished with a lower bonus or even dismissed. The main reason most employees stay is the above average financial compensation they receive. At a certain moment top management insists that all middle managers should attend a workshop with their direct reports in order to learn to think and act more ‘entrepreneurially’. The workshops are to be led by the middle managers themselves, who experience daily that they are not empowered or even trusted, but are continuously controlled by their (top) managers. This is also visible to their direct reports. The half-day workshops turn into politically correct, but embarrassing rituals. The only people happy to attend are the external facilitators, who are paid a fixed fee for every workshop they support…

- Change fatigue – Every effective change requires emotional and sometimes intellectual effort on the side of the employees to internalize and embrace the change. If this effort is experienced as useless due to the superficial, ‘flavor of the day’ nature of the change, employees may not just become cynical, but may also become emotionally tired. This means that the organization needs to put more and more effort in order to mobilize the workforce for new ideas and initiatives. This phenomenon is not unlike drug addicts whose bodies need ever-higher concentrations of the drug in ever-higher frequencies in order to experience any effect.

How to select, time and design the right change initiatives?

Surveying all the comments above, the question is how to distinguish functional change initiatives from non-functional ones. The answer is that decision makers can apply six easy tools to prevent wasting resources on change initiatives that are doomed to be unsuccessful.

- Review the corporate history – Analyze earlier change initiatives in the organization: what were the reasons behind their success or failure and which lessons can be derived from them? This analysis should be executed preferably by an Internal Audit organization or by an external party in order to ensure the right degree of objectivity.

- Be careful when considering fixing something that is not broken – There is quite a distinction between complacency and overzealousness. A critical look regarding one’s own organization, its structure, processes, products, culture, systems, etc. is good. However not recognizing when ‘good enough is good enough’, is bad. This is especially true for support functions within organizations. In order to streamline their processes and lower their (functional) costs, a number of support functions quite often shift work to their (internal) clients through the introduction of self-service tools. As a result of this there are a number of companies in which employees book their own travel, create their own purchase orders, register their own visitors, book their own expenses and sometimes even hire their own staff without the help of HR. Apart from the costs support functions usually make to put these tools and processes into place, it is also the question whether these tools make the work environment for the average employee more efficient or not, especially if the frequency in which these tools or channels are used is low or if the tools themselves are not ‘user friendly’ (which, cynically enough, they quite often are not, …due to cost reasons).

At a certain moment there were so many initiatives going on in a large multi-national Oil & Gas company, that it became a distraction for the day-to-day operations on a specific production location. As a reaction, local management decided to announce an ‘initiative holiday’ to re-focus the attention of the workforce on their core activities.

- Identify hidden costs – Expose and calculate the ‘hidden costs’ that were mentioned earlier in this article and incorporate them in the business case for the change initiative. Evaluate whether the expected benefits are ‘real’ and will be experienced as such by the different stakeholders, and what the hidden and non-hidden costs are in terms of money, manpower, focus and motivation.

- Apply a holistic view – Do not look at change initiatives in isolation, but take the whole landscape into account. It is not uncommon for large organizations to be ‘swamped’ by an avalanche of change initiatives stemming from different functions in the organization. It is the role of leaders to maintain the oversight and insist on a disciplined approach. If they fail to do so it is highly likely that the different initiatives may overlap (a great source for confusion) or even start to compete with one another (leading to spoiled energy and loss of focus).

- Timing – Evaluate the timing of the initiative critically. Perhaps the initiative itself has its merits, but the timing might be completely wrong.

- Transparent costs and benefit tracking – Institutionalize periodic tracking of the costs (including the ones that used to be ‘hidden’) and benefits of the change initiatives and report on them. This threat of having to report in this way will serve as a ‘healthy discouragement’ for those in the organization who want to undertake change initiatives without thinking them properly through.

Conclusion: Less is more

Change is essential for organizations to survive. However, too many non-functional change programs can harm the performance of organizations. Therefore the motto ‘Less is more’ should also be applied to the area of corporate renewal: a few focused, well-designed and profoundly implemented change initiatives are usually much more beneficial for an organization than a myriad of different and potentially overlapping and competing initiatives.

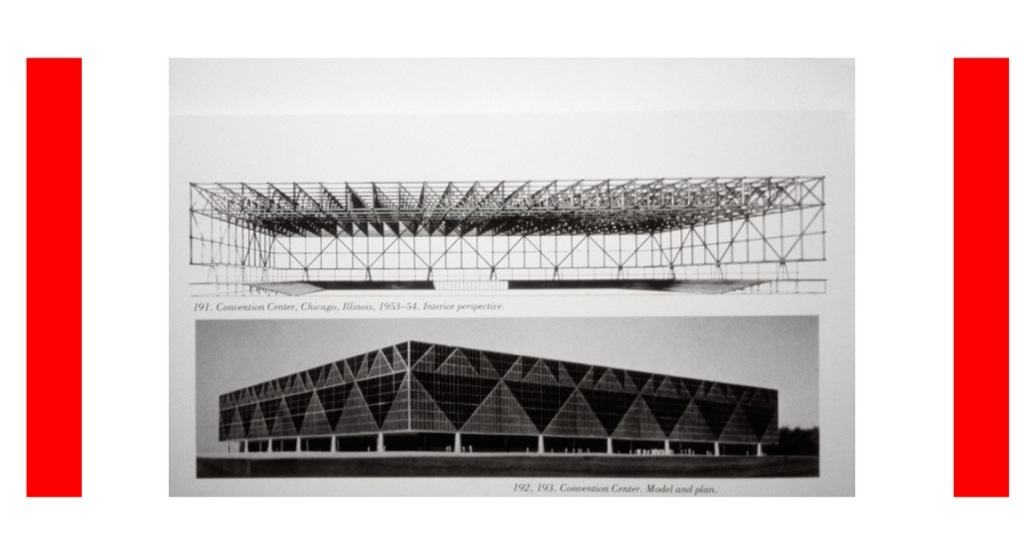

Notes: The motto ‘Less is More’ was is attributed to architect Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, and was used by minimalist designers and architects to describe their design philosophy. This philosophy comprised of the desire to create simple functional designs and structures, using as little parts for this as possible. This was achieved by having certain elements perform more than one function (e.g. glass walls).

Copyright © 2010 Dirk Verburg – Article originally published on Xecutives. net. Updated over time.

Picture credits: Slide of a drawing for Convention Centre, Chicago, by Mies van der Rohe. Abalos & Herreros fonds. Canadian Centre for Architecture, Montréal; Gift of Iñaki Ábalos and Juan Herreros

Discover more from Dirk Verburg

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.

One thought on “Less is more: The hidden costs of change in organizations”